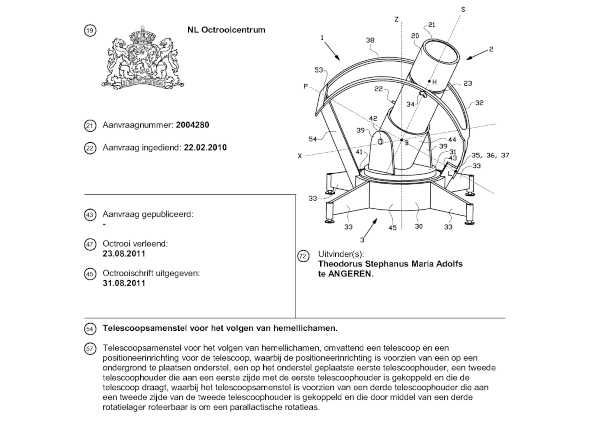

In 2011 Theo Alolfs was granted a patent for a telescope mount that was based on four axes.

With this single mount Theo successfully combined elements of both alt-azimutal - as equatorial mounts. A true hybrid of both worlds.

Every patent has its history. This is the part that I (the author of this website) can reproduce. The previous picture shows Theo's first, in 2009 tested prototype. It's a pitty that many of essential elements in this prototype aren't shown well. The driving force in this construction came from a strong spring that was trying to release air from a large air filled bag which was kept under pressure by the spring. A valve driven by a small mechanical clock only allowed the air to escape at such a speed that the spring could rotate all parts of the construction with precisely the siderial angular velocity of the telescope around the polar axis. Clearly, this mount could carry a fairly large Newtonian telescope, it would not suffer from field rotation and the construction could be built very rigid. Theo had taken long integration picures of M42 with this mount.

For me, the story starts with John Arts, who contacted me. He said he knew of something that he thought that I should see. I had no idea of what and he didn't give much explanation, but it clearly had to do with astronomy. There was only one condition: I had to promise my secrecy of what I was going to see. I was picked up at home, although I wasn't blindfolded, I do not remember where I ended up. I was brought to the place where the above depicted mount and its creator were. I was introduced to Theo Adolfs, and I was introduced to something they said that was a telescope mount. I was totally amazed, flabbergasted and maybe still in denial. All I could see was a pretty complex construction to carry a telescope. It didn't look like anything I had seen before. He demonstrated how the axles would move, and that driving the polar axle would force all other axles to follow. One source of force was capable to drive everything in the construction to enable equatorial motion. The mount did not require a field derotator. I could see by the motions of the construction that it was fit to take long integration pictures, but I had hardly an idea why it could function.

Theo Adolfs had a partner with whom they were investigating their chances to successfully file for a patent. I was asked for my comment. Clearly, the mount was sturdy enough to carry a fairly large Newton telescope. Large telescopes are often found on to flimsy telescope mounts that are easily excited by wind gusts. They come to high amplidude vibration with low frequencies and they will take several seconds to dampen out. This mount did not suffer from that, this had the stability of a Dobson mount. And it was capable to take pictures without field rotation. In the world, there are many Newton telescopes in use with excellent optical quality, but most of them are not used for astrophotography. Only because of the quality of the telescope mounts. I certainly did believe it was new and that it could enable the usage of Newton telescopes for astrophotography.

I didn't need any persuasiveness to suggest Theo a drastically simplified design. Of course, motors - preferably computer controlled - had to provide the driving force. I also explained that if you want a product to be accepted by many users, it should consist of at maximum seven easily distinguishable parts that are put together in a simple way.

Theo was granted his patent, but it didn't stop there. He evolved his first prototype to a very nice design that brought even more improvements. Two horseshoes made up a cradle that carried the telescope. Theo also exchanged the large bow in the patent for a fork. The fork was attached by a small bow shaped construction to the centre of the azimuthal base. This bow allowed adaptation for the latitude. Although the second prototype was constructed a little to small, Theo had seen that a mount according his new idea could point a telescope to any part of the sky, it could trace objects without meridian flips, it did not suffer from field rotation. And it was able to trace circumpolair objects forever, without interuptions.

Theo and his partner came in contact with Synta, the manufacturer of Skywatcher and Celestron. Synta was interested to see if Theo's idea could be developed in a commercial product. Theo received a steppermotor with a control unit fom Synta. The motor was attached to the polar axis.

His invention soon evolved into a tested prototype that was capable to track celestial bodies anywhere above the horizon without suffering from meridan flips.

The working principle is based an that of the universal joint.